was added after artist died, art museum agrees

Florida A&M prof discovers mystery; Cincinnati museum puts painting under scope

Where did the 'phantom artist' find his inspiration? We show some clues here.

By Michael E. Abrams

Copyright 2009 / new material added

•See also article on discovery of Hebrew text 'I am the Lord thy G-d' on this painting

A famous painting of Madonna and Child almost five centuries old was apparently repainted by a phantom artist to add a famous, miraculous flower that grand master Joos van Cleve probably did not ever see or hear about in his lifetime.

The apparent resolution of a riddle involving this painting reinforces the need for the application of botanical history to paintings. It also shows how some detective work along with modern museum techniques can alter the story behind even the most famous paintings.

Sprouting from a red carnation held by the Madonna, the passion flower has been regarded as a focal point of this particular Madonna and Child painted by the Flemish Renaissance artist. He finished this work between 1530 and 1535, according to art historians.

| But,

unless

he

had

exclusive

knowledge

from explorers of the New World, van Cleve, who died ca. 1540, could

not have painted the

flower. Reason: it first appeared in drawings in Europe about 70 years

after

his death. I discovered this anomaly in the van Cleve painting in the summer of 2006 while writing an essay on the symbolism of the flower and the Kabbalah. I have photographed passion flowers many times in Florida, where I am a journalism professor at Florida A&M University. I was researching the history of the flower in religious art, when happenstance led me to the van Cleve painting. I realized it could not have been painted in the 1530s with the red passion flower in it. How the flower got into the painting is a mystery. The verdict by museum officials is that the painting was enhanced perhaps 70 to 150 years after it was sold by the painter. So far, what has happened may not change the history of the difffusion of knowledge about the passion flower in Europe, but it may alter forever what critics and viewers say and know about the painting: it comes with a caveat. The mystery was buried in history So, Joos van Cleve, who lived from approximately 1485 to 1541, died 70 years before he could have seen the flower. As it is, the flower is still apparently painted from rumor by the mystery artist who altered the van Cleve. If the passion flower were truly van Cleve's, it might have have caused historians to rethink the story of the spread of religious iconography in Western Europe during the Renaissance. It would revise history to think that van Cleve, who lived in Antwerp, had specific knowledge of this new flower which was discovered in the New World perhaps a few years previous to his death. A few, if any, of the clerics who may have returned to Spain from the depradations of Cortez and others, would have been able to describe the nature of its potent religious symbolism. The painting, up until today, was either a clever deception, or a work so unique in its time as to stand alone among thousands of paintings of Madonna and Child by the great artists of the world. A companion painting, almost a cookie-cutter, can be found in the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri. It contains everything but the passion flower. Another such painting is held by a museum in France. The Cincinnati Art Museum painting looks very much like a deception at this point. "We looked at the painting briefly under a microscope and the findings more or less confirm my scenario where the flower was painted by a later hand," said Andy Haslit, a curator at the time we discovered the passion flower. The painting has resided at the museum since 1981. "We found that the black background was painted around the carnation, where the passion flower was painted right on top of the black, thus indicating that it was done later." "Also, the modeling of the paint (i.e. the way that the artists built up a volumetric representation of their respective flowers) is entirely different," he observed. "The carnation has a layer of dark pink paint under a layer of lighter pink, giving it volume and shading, while the passion flower is done in simple red with no shading or modeling. " "All of this means that the passion flower was a later addition by a different hand. We also can tell that it wasn't too much later, because there are cracks that run continuously through the background and the passion flower. " "These cracks would have formed somewhere around 100 years after the painting was first made (with a wide standard deviation that depends on humidity, lighting conditions, etc. etc. - it could be 70 years, it could be 150." Why would a mystery artist have added a passion flower? To understand what we can about the flower and why someone might have added another holy symbol to a religious painting, perhaps we must first consider the vested interest of the Church in the prospect of saving souls through the story of the passion of Christ. For the illiterate millions, symbols were necessary, and the Church was about symbols, from the cross to the rosary to the icons in the cathedrals. Rome also sought proof of the veracity of its faith through the works of nature. Floral symbolism is essential to understanding the history of painting. Violets, for example, represented humility. The passion flower, along with pure white lilies and blood red carnations, became symbols for the purity of faith, the tears of the Virgin Mary, the crucifixion. The passion flower represents the passion story, the story of the crucifixion. Consider the shape of these essential parts of the flower. The three stigma or female parts, spill from the top of the flower, and represented to the Holy Roman Church the very nails of the cross. They also may represent the Trinity. The five circular and recumbent male anthers spoke of the five terrible wounds suffered by Christ. The many dainty fringes of the corona of the flower were bloody lashes of the Roman scourge, meant to hasten the death of the man condemned to die on the cross. The 5 sepals and five petals represent the 10 disciples who witnessed the crucifixion, minus Thomas and Judas, who were elsewhere. The Moche, the Aztecs and the Passion Flower The earliest depiction of a passionflower we can find is from the mysterious Moche culture of northern Peru. The civilization is estimated to have flourished from 100 C.E. to 800 C.E. It is a ceramic jug handle depicting the fruit of the banana passion flower, dated about the fifth Century C.E. and is found at the Museo Larco in Lima.  The passion flower was first called Flos Passionis by the awestricken (and quite inventive) friars who found it in Mexico, Peru and perhaps Florida. Varieties of the beautiful vine have an aromatic fruit – called the granadilla in South America and the maypop further north. A religious poet at the end of the sixteenth century wrote of the flower as proving to the new native American believers "the torture of God." An abundant summer bloomer in the New World, the flower encompasses hundreds of species from Peru to Virginia. The flower may have actually appeared in the 1552 Aztec Codex Badianus, which was kept from view for 400 years. The illustration, however, may have been of a dahlia rather than a passionflower. This otherworldly flower blooms today on its clasping vine this hot sticky summer across Mexico and the eastern United States. Its pungent, tart fruit will be grown from Australia to Hawaii to much of Latin America, sold in markets and groceries, and processed for juices such as Hawaiian Punch. The riddle was framed by impossibilities "I find this seventeenth-century addition scenario to be the most plausible," said Haslit. "Also, I see no reason at all to think that this painting is not by van Cleve, and neither do the van Cleve people that I've read. What we now know is that the passion flower part only is not by van Cleve." It is most probable to this writer that the flower would have been added before 1620. That's when the rumors of its miraculous existence were supplanted by the real flowers, having been grown in gardens of botanists in Europe. The story of the discovery of the passion flower in "New Spain" compelled Jesuit missionaries in 1608 to bring a color drawing and dried plants from the New World to the powerful Pope Paul V, the same pope who presided over the trial of Galileo in an age where churchmen burned witches and heretics. Spanish physician and herbalist Nicolas Monardes, writing about 1570 and revising later, described the flower's herbal powers and its supposed relationship with the Crucifixion. He had never visited the New World, and relied on reports from those who had traveled there, perhaps someone who had traversed the ocean in the bloody and remunerative voyages of conquest of Cortez in the 1520s. However, Monardes, who used woodcuts of other flowers in this 1570s- 80s book, included no drawing of the flower. Monardes writes that it was being grown in Seville (see page of Clues). However, we have discovered no evidence that the New World explorers brought an illustration of the flower, other than the stylized Aztec codex (1552) back to Spain before the early seventeenth century. And that codex was not circulated. Emil E. Kugler and Leslie A. King in Passiflora: Passionflowers of the World (Ulmer and MacDougal, Timber Press, 2004) write that sheets of drawings of passionflowers, similar to church scholar Giacomo Bosio's depiction in 1610, were printed in Germany and Italy in the later 1600s. Based on rumor. he placed a false crown of thorns at the top, quite similar to the suspect depiction in the van Cleve painting. These, the authors state, "were the first representations of the passionflower to appear in Europe." Kugler wrote that he considers it "extremely unlikely, that about 1530 a Flemish painter - who never visited America- derived the symbols of his own accord and depicted them in one of his paintings." "A precise analysis of the part of the painting in question could produce signs of a later supplementation, which I consider quite probable." There are no records of such an earlier drawing. Joos van Cleve would probably have looked in vain for a drawing of the passion flower. Indeed, such a flower is not found in the first editions of the Herballs of the Flemish physician Carolus Clusius, in 1601, or of the British John Gerard in 1597, two of the pioneers of such illustration, well after it was mentioned by Monardes. The first flowers to resemble nature's work appeared somewhat later. By 1614 French botanist Jean Robin had grown passionflowers in his garden and engravings show very accurately the Passiflora incarnata, write Kugler and King. The British herbalist John Parkinson in 1629 included a realistic drawing as well as a fanciful Jesuit sketch. Dedicating his book to the Queen, herself a gardener and certainly a Protestant, Parkinson took pains to debunk the clerical representation of the flower. Parkinson knew it to exist in Virginia and called it the Virginia Climer. By that time, the flower had been planted in gardens in Paris and London, say King and Kugler. The first known painting of the flower by a European artist occurred about 1625 when the Jesuit Daniel Seghers added it to a garland of flowers embracing a cartouche of angels. This painting hangs in the Louvre. Sam Segal, an authority in the world of painting and botany, pointed us to the work. But no one, including John vanderplank, author of the lavish Passion Flowers records a drawing in the 1500s from which van Cleve might have worked, even if he knew about such a flower. "The early drawings have always fascinated me," wrote John vanderplank, who is probably the foremost botanical authority on the flower. The spear shaped leaves in some of the early drawings, and black dots on these drawings (30 of them representing the infamous 30 pieces of silver) were probably because those who drew the pictures never really saw the living plant, he says. "All they had was a wonderful story and dried flower (herbarium specimen) and if you look at herbarium specimens they are often spotted with fungus and the position of the stamens (wounds) is compressed onto the corona filaments instead of being just below the ovary, just as in your painting," writes vanderplank. He said that some years ago "a lady from some university in the USA" sent him some photographs of engravings on an antique Mexican "salva and bowl" possibly from the 1500s, and said she was going to publish an article, but never did, he said. These may have been early representations of the passion flower. And so, based on physical as well as historical evidence that can be established in the year 2006, the passion flower in Madonna and Child by Flemish Renaissance artist Joos van Cleve is a deception. Transported to the New World by the Devil In Mexico and South America, after Columbus's voyage in 1492, priests who traveled with Cortez and others were apparently using the newfound miracle flower to attempt to persuade the native peoples of the majesty of Christ. It quickly assumed mystical powers. The flower, a poet opines, was present at the crucifixion, and was transported by the jealous devil to the New World. Perhaps the flower was used in time to save some of the "Occidental Indians" from the fires of Hell. Maybe it worked for some. The bloody, merciless destruction of these ancient Indian societies by the Spanish conquistadores is seared into history. It was retold by William H. Prescott in the classic The History of the Conquest of Mexico. An eyewitness to the slaughter was Bartolome de las Casas in A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies. What accounts there were sometimes reached the ears of sympathizers, and the Church asked that the Indians be treated as human beings capable of seeking salvation. But this message was not heard by those who wished to exploit this new land. In Europe, the cathedrals drew the population to mass. The Church was increasing its wealth through sales of indulgences. Religious people, and perhaps the new middle class, were the customers for paintings of the Madonna and Child. Perhaps he world has not changed much, as we hear of starvation and tragedy in our world, and see it on television, yet often feel powerless to do anything. It may be that the Devil is still lurking. Suspicions were reinforced by research A curator of special collections at the University of Wisconsin in Madison and an art historian who directs Princeton's Christian iconography collection could find no illustration of this flower in early church iconography in the 16th Century. The writer could find no Madonna and Child with a passion flower -- except for van Cleve's purported flower --in a search of hundreds in the 16th Century. If it were genuine, botanical and Church history would had to have been be rewritten. As in other Madonna and Child paintings, the iconography is there. The beautiful child-man with orange curls is holding ripe cherries, a fixture in van Cleve paintings and symbol of resurrection and possible paradise. The Christ child's eyes focus upon a blood-red carnation with leaves of sweet-smelling rosemary and another strange symbolic item growing out of its petals - a single red passion flower. The carnation, Christian legend says, first bloomed from the tears of the Virgin Mary as Christ carried the cross. The passionflower prophecizes his sacrifice to come -- the crown of thorns, the wounds, the lashes. It is a tumultuous prediction, one that will change the world. On the table is an apple or a quince, often seen in these representations of virgin and child. If an apple, it represents the temptation of Eve. White lilies and roses are sometimes seen, as well as grapes, a symbol of the sacrament and sacrifice for sins. . Did a Churchman alter the painting? In Europe, the flower could also be used to resymbolize the power of the Church as the Reformation began to appear and dissenters and disbelievers were hunted out and excommunicated or murdered by the millions, in both Europe and the New World. History tells us of the slaughter of Protestants in Antwerp in 1576 in an event dubbed "The Spanish Fury." Six thousand residents of Antwerp were slain by Spanish soldiers, angry that they hadn't been paid for years by their king. One might imagine an owner of the van Cleve, in an effort to waylay an inquiry into his beliefs, contracting an artist to add the passion flower to the van Cleve painting. Perhaps a functionary in the Church ordered the change in the painting. Perhaps the flower was added to the painting by a thankful nobleman, such as depicted by the later Rembrandt, whose family might have escaped a recurrence of the black death. A still, small religious voice reaches out from the painting, and that voice speaks to us today of the depth of belief of those who witnessed the world before science drained it of the utterly miraculous, where death and wretched disease were constant companions, and where the Church held the key to the only happiness that could exist. Grown by the Maya and Aztec for food, ritual Grown for its sweet, tart, perfumed fruit by the Aztecs and ancient native cultures which may have noted its sedative powers, the flower was found in places variously described as Florida, Peru and Virginia. It is possible the flower was used in ritual. The precious and incredible frescoes at the ancient site of Bonampak in Chiapas, Mexico, dated about 790 A.D., show a Mayan official apparently wearing a flower headdress which suggests that these vines were used in dress for ritual in meso-America. Known as the "maracock" by native Americans The Passiflora incarnata, which blooms in the United States, was noted by the famous Capt. John Smith in Virginia as grown by the native Americans for its fruit. The Indians called the fruit the "maracock," he wrote in his diary. The seeds of this fruit have been discovered in archaeological digs in Creek encampments in the southern U.S. The flowers bloom not far from ancient Indian mounds in our community near Lake Jackson in Tallahassee, Florida, where one may imagine pre-Columbian Indians farming the plant, as perhaps the Apalachee tribes did at the time of the De Soto exploration of Florida. They were food for the Apalachee Indian tribe at Mission San Luis, the largest Spanish mission west of St. Augustine in Florida, 1656-1704. (continued in column to right beneath photographs or simply CLICK here) |

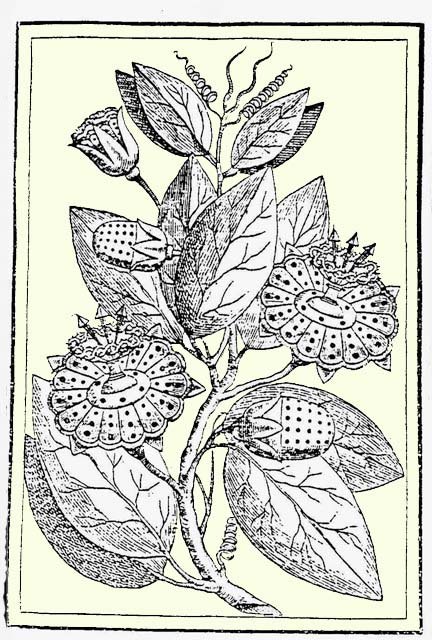

Joos van Cleve's Madonna and Child, with flower in question at the left. It sprouts from a red carnation, with leaves of rosemary also sprouting from the carnation. The carnation and the rosemary also have symbolic properties in other religious paintings. Rosemary is not unknown to sprout from carnations in a few Renaissance works. Below, an enlargement, showing the crown of thorns, typical of the much-later rendition of the flower by the Jesuits. Photograph provided by the Cincinnati Art Museum The painting was a Centennial Gift of the Cincinnati Institute of Fine Arts.  Enlargement of the Passion Flower. from the painting, dated 1530-1535. Where did the mystery artist get his passion flower from? See our special page of comparisons. Below, the drawing by church scholar Giacomo Bosio circa the year 1610. This flower shows an imaginary crown of thorns around the stigma, as do other drawings by churchmen at that time. Mauro Serricchio of the Passiflora Society helped us to obtain this picture.  Below, Passiflora incarnata, one of hundreds of species, thrives in the eastern United States. It was mentioned by Capt. John Smith in his writings on Virginia and depicted true to natural form in 1629 by John Parkinson, Paradisi in Sole, Paradisus Terrestris which was published in London. See "Clues" page for Parkinson. Photo by Michael E. Abrams, copyright 2006.  Fruit of the Passiflora incarnata in the Eastern United States is below, and tastes sweet and tart.  Granadilla, below, the fruit of another species, is grown in the subtropics for its luscious flavor and juices. Its fragrance is used in lotions and shampoos. Its calming, sedative properties are found in teas, health products and medications.   Photos of flower, fruit, copyright M.E. Abrams Outcome of the Inquiry Many people in the art and botanical worlds have described the story of this painting as worth exploring. The painting, itself, has been substantiated as van Cleve's by such authorities as van Cleve biographer and expert John Oliver Hand and the late art expert Max Friedlander. That the painting is his, is not in doubt. The passion flower had been accepted as authentically van Cleve's. Hand, curator of Northern Renaissance paintings at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., is currently the foremost authority on van Cleve. "I'm sort of surprised," said Hand. "I hadn't thought about (the painting) for a while. It's an interesting thing to know." "I looked at the website and think it's quite possible that this passion flower was added later," said Hand. Somebody else apparently came in and worked on the painting, he said. Hand said the true determination is the physical evidence established by the Cincinnati museum. The work, itself, remains a high quality piece by the artist, he said. He said that could think of no other painting of Madonna and Child of the same era that had a passion flower in it. The painting in the Kansas City museum, much similar, could be sort of a clue. It did not have a passion flower. Hand said he had thought it "very odd" that one flower would "proliferate" out of another, and had he more time, he might have looked further into it, but that he was following his source material. In his recent biography Joos van Cleve: The Complete Paintings (Yale University Press, 2004) writes that the passion flower in the painting "has been identified as Passiflora caerulea, a New World plant whose blossom uncannily appears to be composed of the crown of thorns, the five wounds, the three nails, and even the columns and styles that figured into Christ's torment. No wonder then that the plant is known as the Passion flower. ." He cited Mark Carter Leach, 1979, in the journal Studies in Iconography in the article Michelangelo Invenit, Joos van Cleve Explicavit. Sparing some leeway for interpretation, Caerulea is actually a white flower, fairly typical of the family, and it could be a stretch to visualize a "crown of thorns" upon it. As in nature, no species of passion flower has such a feature subtending its stigma. Curator Andy Haslit of Cincinnati suggests the artist of the mystery flower was taking its symbolic value above its botanical value, and that is "artist's license." Mystery artist may have never viewed the flower It is, however, possible that the mystery artist had never seen a passion flower, and that it would have been painted from rumors passed this way and that in the 17th Century, whispers of wonderment set afire by the fevered religious imagination. Or, perhaps the red flower was fashioned from a woodcut based on threads of rumor. It is so plain, so rudimentary in form that it is still one of the first representations of the flower in Europe. Curator Haslit (he has since left the museum to study for his doctorate) says that it was not uncommon for paintings to be altered. The similarity of the van Cleve flower to a 1600's woodcut impresses him. "I'm saying the passion flower is close enough to the woodcut to be directly from it." "The idea of this being altered is fairly common as tastes change," he said. People did not have a modern sensibility toward paintings, and "they would have no more compuction to adding on to a painting as we would to adding on to our house." For example, a Titian, owned by the museum had been heavily reworked, he said. It was a portrait of Phillip II, a Hapsburg. One artist added a crown, another a scepter, and another put him on a throne. The Vatican museum, as another example, decided to "fig leaf" all of its statues in the 1800s. Up until 50 years ago, it was common to hire a restorer who was actually an artist who would repaint over an original, said Haslit. Barbara J. Sussman, a member of the American Society of Appraisers, said many paintings have been altered because of "the fashion of the times." However, she said, "One would never consider making an alteration to a painting today, as the education and appreciation of art has increased and awareness for the work in its purist state is always being sought." "In my opinion, purity rules." Sussman's clients include the New York Historical Society and the Yale University Art Gallery. (http://www.sussmanart.com) Rembrandt was altered, then restored In 2003, a Rembrandt came to light, she said. This rediscovered work showed an elderly woman in a white cap with a fur collar. The fur collar, investigation showed, had not been part of the original painting and was added later to make the portrait "a woman of class rather than an elderly servant." The painting was painstakingly repaired, and sold at auction at Sotheby's for $4,272,000. Restoration increases the value of a painting. Van Cleve painted in Antwerp in the Netherlands, a bustling commercial center for the time, where ships came in from all over the New World. As the economy boomed, painters moved from selling on commission to putting their wares into the marketplace on speculation of a sale, explains John Hand. van Cleve had a workshop and helpers, as did many artists. This explains the similarity of paintings by any particular artist - if a painting sold well, why not paint a similar one? Thus, the painting in the Kansas City museum sans passion flower, and another one, in a museum in France. We discuss the three madonnas here and our recent discovery of what may be Hebrew script on the Cincinnati madonna painting. The van Cleve provenance: it can be traced from 1913 in Munich, "bounces around Paris a couple of times" and winds up in a collection of E. W. Edwards who gave it to the museum in 1981. A van Cleve was auctioned for a half-million dollars in 1993, and recent pieces have been auctioned from $100,000 to $350,000. Four years ago the Madonna of the Cherries went for $222,572 at Sotheby's. All that Haslit can say about the painting's value, under museum rules, is that "it's worth more than $10." How much money it is worth may be up to the market to determine some day. Its real worth is in the heart and imagination of those who gaze upon this Madonna and Child.

|

|

|