| Personal Observations Kabbalah, mysticism may be envisioned in a strange, otherworldly flower Further recommendations for Reading are listed below |

FLORIDA WILDFLOWERS |

||||||||||

By Michael E. Abrams Copyright 2009 What's in a number? Numbers are clues in the mystic world of Kabbalah, the medieval writings that have become a focus of attention today in a revival of things of the spirit and soul. In Kabbalah the mysterious spectacle of the universe is explained and made whole. Secrets are made free.

Kabbalah spins and weaves the letters of the Hebrew alphabet in mystical ways that relate words and ideas to each other and to the fervant religious imagination. Reinterpreted from the Hebrew and Aramaic writings, many of them obscure and recondite, Kabbalah, it is argued, goes back to concepts formulated in the first century by Rabbi and sage Shimon Bar Yokhai, a mystic and disciple of Rabbi Akiva, martyred by the Romans. Bar Yokhai hid in a cave for 13 years until it was safe to return to Jerusalem, where he taught his followers the secrets of mysticism. But these legendary teachings were largely untapped until the 13th Century,when there appeared a book of writings called the Zohar or Book of Radiance. Some attribute this book to one Moses de Leon. Uneven and some would say of dubious authenticity, the Zohar nonetheless regales readers with tales of rabbis and the story of a light-filled universe exploding into 10 dimensions, and of the possibility of great spiritual insight. Popular centuries ago, a few of its concepts are used in prayer books today. Pop Culture of Kabbalah In truth, kabbalah was neglected by most, save a few rabbis and scholars, and a novelist now and then. Kaballah had fallen into disuse, like once-treasured but now forgotten jewelry in a chest in the attic. But someone spilled the contents, and found that it contained a message for a fragmented society. Once light hit the rubies, the refracted beams seemed a cure-all for modern ills. The pop-culture of Kabbalah, and the hundreds of books hot off the press belie the stiff undergirding of serious study required even before one begins Kabbalah. Movie stars and pop sensations Madonna and Brittany Spears claim that Kabbalah has revitalized their lives. Add to that list celebs Demi Moore and Paris Hilton. Madonna, 'the material girl,' is on tour, where she sings and dances with the symbolic red string on her wrist to ward off the evil eye. Good seats sell from $1,000 to $6,000 each. The age of 40 must be attained, say the rabbis, before one has the maturity and learning to venture into the hidden mysteries of the cosmos with proper restraint. Otherwise, the usufructs of Kabbalah, divorced from its religious context, may be sparse and even misguided. For what it's worth, Madonna, a Leo with Virgo rising, reached the venerable age of 50 on Aug. 16, 2008. Mystical Readings Undeniably, the pathways that criss-cross concepts, words and numbers can inspire, inform, and sometimes transform. The ancient and challenging numerological study, Gematria. is closely related to Kabbalah and its prescription for illumination. For every word, there is a number, and for every number, there are, indeed, many words. And so this article reaches tangentially into the cookie box, but merely touches upon some concepts which truly require more time. The nature of religious learning should not stop one from delving into concepts, we think. The Pope Viewed The Flower Discovered by the Spanish conquistadores, the passion flower was first described by Spanish explorer Cieza de Leon. That happened in 1553, in Colombia, write Emil E. Kugler and Leslie A. King in "A Brief History of the Passionflower" in the book Passiflora - Passionflowers of the World by Ulmer and MacDougal (2004, Timber Press). Spanish physician Nicolas Monardes, in the late 1500s, listed the grenadilla in his famous book on plants and herbal remedies, write Kugler and King. Spanish Jesuits handed a curious Pope Paul V some dried plants and a color drawing in 1608, write historians. One early popularizer was the ecclesiastic historian and cleric Jacomo (or Giacomo) Bosio writing in Italian in 1609. The Spanish friars named it, said Bosio, "La Flor de Las cinco Llagas," the flower with the 5 wounds, for five red spots adorned on the species he described. Reports of this “stupendously marvelous” new world flower which told the story of Christ's crucifixion, were disbelieved by a skeptic church until plain evidence was carried to Rome, writes John Vanderplank in his profusely illustrated book Passion Flowers (MIT Press, 2000). Represents the Crucifixion The ten petals and sepals, to the Spanish, represented ten disciples present at the crucifixion. The three stigma represented three nails on the cross, the five anthers the five wounds of Christ. The many fringes represented the crown of thorns in the passion story. Bosio counted 72 fringes or filaments, which according to tradition, writes Vanderplank, is the number of thorns in the crown of thorns. A poet of the time explains that this flower was used to persuade Indians of the power of the cross. The passion flower, he writes, was a witness at the crucifixion. But the powers of Hell, in shame, carried the flower away to the New World. This usurpation was to no avail, as the Indians "whose faith now is similar to ours" were now empowered to read of "God's tortures in that holy flower." This lovely fruit was cultivated by native Americans. It was reported in North America in 1608 by Captain John Smith (of Pocahontas fame) in his diary as the "maracock - a wild fruit like a lemmon." In Florida, the Apalachee Indians left seeds, archaeological sites show. The maypop was among the wild fruits eaten by native Americans at the San Luis Mission (near present-day Tallahassee, Florida) and even before, at prehistoric Indian sites. Archaeologists discovered maypop seeds at the Mission San Luis de Apalachee site (1656-1704) in Tallahasee. The native Apalachee plant diet included maize, brean, squash, sunflower, persimmon, grape, maypop, saw palmetto, cabbage palm, plums, blackberries, hickory nuts, acorns, chinquapin and beech. The Spanish brought and planted the old world crops of wheat, garbanzo, peach, watermelon and fig. At Lake Jackson in Tallahasee, Florida, the maypop or fruit of the Passiflora incarnata grows prolifically. The lake is the site of Indian mounds dated 1000-1500 A.D. (See essay Plant Production in Apalachee Province by C. Margaret Scarry in The Spanish Missions of La Florida, University of Presses of Florida, 1993, edited by Bonnie McEwen). The incarnata so enamored Europeans that it was planted in Paris by 1612 and in Rome by 1619, write Kugler and King. Herbalists, perhaps learning first from Aztec or Mayan lore, noted a tranquilizing, sedative effect of the passionfruit. To this day, parts of the plant are used in soothing teas and other herbal remedies. Locked into History A more ecumenical name change for the family Passifloraceae, a name appended for historical reasons by the Swedish botanical genius Carolus Linnaeus, is not in the offing. Given the nature of the science of taxonomy, such changes seldom, if ever, occur. Freighted with a Latinate gloss of centuries of botanical enterprise and some intrigue, it was set in order by the Swedish "father of taxonomy" in the mid 18th Century. Linnaeus, a pious man who learned botany in his medical education, held a strong belief in natural theology. Proof of the existence of a divine being was evident in nature's construction, a theme that motivated the learned botanists of his time. Rectifications in nomenclature that are made in today's world are made slowly and deliberately. So much plant description simply seems locked into history. The general public has no more sayso in this honorific Latinization than the insects, spiders and bats who familiarly pollinate the plants. Scholars must present scientific botanical evidence of new discovery, or indisputable historical findings to the International Botanical Congress of the International Association for Plant Taxonomy, headquartered at the University of Vienna. And we are not even whispering that the name of the passion flower should be altered -- for it means so much to too many people. But we would like to engage in some speculation about the naming of flowers, and how what we come to know about them is so closely attached to how they are named. Continued at top right |

Photos copyright M. Abrams Passiflora species are now grown around the world. The Kabbalah Flower, or the Flower of the Zohar History suggests that what we call our plants and animals follow the first names bestowed upon them by explorers, although surely the natives possessed their own words. Some speculate that the word describing the new world bird "turkey" first came from the lips of Luis de Torres who was escaping the Spanish inquisition and who sailed with Columbus. The word is from the Hebrew word "tukki" which describes a large bird in the Bible. What if the passion flower had been first described by a Spaniard familiar with the Kabbalah? Many exiles fled from Spain. The inquisition began just as Columbus sailed. It could have happened. We may have some entirely different aspects, for it is a flower most representative of a kabbalistic interpretation. Meadow of Passion Flowers The Passiflora incarnata in North Florida, decked out handsomely to attract the bees and butterflies, is as showy as most of the 500 or more species. It is known as the maypop or apricot vine with sweet fleshy seeds like a pomegranate With a signature five green sepals and five diaphanous white petals, it boasts three lemon-yellow female stigmas, five greenish male anthers and a corona of more than a hundred purple filaments.

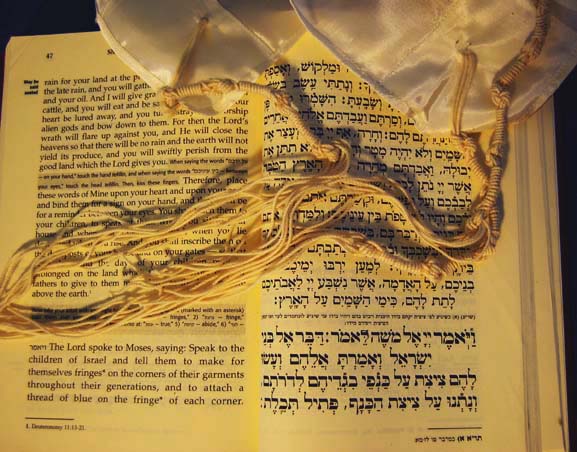

The purple grenadilla fruit is cultivated all over the world. It is a thriving industry in Australia, New Zealand and Hawaii, as well as its native South America, and flourishes from Jamaica to Israel to India. Explorer and environmentalist John Muir, wrote of the passion flower as having "the most delicious fruit I have ever eaten." The sweet flesh surrounding the seeds is strained off to create the juice. Gematria of Wildflowers Flowers and special plants loom in passages of Torah and we especially like to browse Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan’s purple Chumash -- the Five Books of Moses in Hebrew -- with its botanical footnotes and drawings of plants. The writings, legends and oral traditions give us much more than Torah, which is sparse with description. It is said Mount Sinai bloomed as Moses was given the Torah, and so homes are full of flowers on the holiday of Shavuoth occurring in the summer.

The passion flowers of almost all species, whose petals range from spicy cinnabar to raspberry pink to autumn yellow to the purest vanilla white, clothe themselves with a circle of delicate and fashionable threads. These flowers reflect the passages within the Shema, one of the most important prayers in the entire Jewish liturgy. Here are the essential bargains between man and G-d, where the relationship is outlined. "Hear O Israel, the Lord is our G-d, the Lord is One." And it is in this essential prayer that Moses was called to tell the Children of Israel to make for themselves Tzitzit (fringes) putting a thread of blue upon the corner fringe. Because the source of the dye for blue has been lost in history, the modern-day Tzitit and the larger prayer shawl, the Tallis, do not have blue threads. Many a Tallis, however, is colored with stripes and shades of blue.

The fringed Tallis is worn by all religiously observant Jewish men in morning prayer. While in conservative and reform congregations, women sometimes wear a Tallis, in Orthodox congregations, usually only the married men wear them. These garments are more than symbolic regalia - they are essential reminders of the special obligation keep one's thoughts on prayer. Some think they are a protection from evil. Touching the hem of such a garment is also thought to have healing power. The fringes may also speak of the explosion of light, a kind of big bang, that is the source of the universe in Kabbalah. One who gazes upon the passion flower to admire its dress of delicate filaments may be mindful of these beautiful threads of prayer. Such a beautiful flower attracted the Spanish, who quickly imagined its possibilities. When they gazed upon the passion flower, they were transfixed by another religious message. Passion Flower Under the Glass We put six of our magnificent specimens into to a vase of cool water and moved one under the lens of a magnifying glass. And we began to examine. Yes, there were the three stigma, the five anthers, five petals and five sepals. The number of these basic elements are the same among the passion flowers of almost all species. Letters, Numbers Speak of Wisdom From the viewpoint of a Gematriast, every letter and every number has a spiritual meaning. The number 'three' for the stigma, may very well represent the names of Hashem (the Most Holy) in the Torah. The number three may also represent "wisdom, understanding and knowledge," the nature of which have garnered such deep religious interpretation that they might require a lifetime to plumb.

The sephiroth are the basis of the Zohar, that mystical and homiletic book attributed to Moses de Leon. Fringes Open a World of Interpretation On this special passion flower, I counted 111 purple and white threads. These delicate threads or corona filaments bring everything into focus, as in a circle. The Hebrew letters Aleph, Vav, Hay represent the number "111." In Gematria, the number 111 has three parts. The number "one" relates to the divine world and the "ten" to a spiritual world. The "hundreds" signify the physical world. Thus we have unity of all three worlds. And in Psalm 111 we read: I will give thanks to the LORD with my whole heart, in the company of the upright, in the congregation. Great are the works of the LORD, studied by all who delight in them. Full of honor and majesty is his work, and his righteousness endures forever. But, in true testiment to diversity in nature, each flower may have its own personality by number of fringes, and its own interpretation. Now, we hasten to say, every flower will not have the same number of fringes, as, for instance, daisies of the same species certainly differ in the number of petals or the old game, 'she loves me, she loves me not' would be rigged. In the year 1609, the churchman Bosio counted 72 on his species of passion flower. These actually coincide with "the 72 names of G-d" and a book by that name by Kabbalist Rabbi Yahuda Berg, a popularizer of Kabbalah whose clients include Madonna. He likens these names to energy fields or mantras or current that flows through life's realities and can solve life's problems. Flowers Embroidered into Ceremony If one were to study the history of the religious significance of plants and flowers, one would see that the Bible has many references. In daily life, the synagogues are often filled with flowers in times of celebration, and hardly an embroidered mantle or silver adornment is without them. A stunning fringed yellow Torah mantle from the year 1750, in a Czechoslovak state collection, is stitched with paranormal, illusionistic orange and yellow flowers that, to this writer, resemble passion flowers. (The Precious Legacy, 1983, David Altshuler editor, Summit Books. p. 126). The fashion of the day was to improvise on Dutch still-life paintings of flowers, say the authors. It is said that Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav taught that each Hebrew letter is like a flower of the field “and from these letters one forms bouquets.” Each word is filled with its own resonance. One may elevate one's soul to the divine presence, write the Kabbalists. Flowers need not represent one religion or another, nor should they, but the many interpretations available should allow us to see that they can communicate symbolically to all of us. And so we may venture into the fields of flowers knowing that what we see is not only scientific -- but can be related to a larger spiritual world -- and that our journey may be enhanced by the joy of observing manifold creation and the oneness of all. We have added a list of recommended readings below. Michael E. Abrams Tallahassee, Florida USA |